Every good blog post must start out with some good-old appeal to authority! A wise man once said:

The reason most (not all) methods don’t add value (over baseline) when scaled is because they’re “extra training data in disguise”, so their benefit vanishes in the high data regime.

— Ilya Sutskever

Sutton’s Bitter Lesson posits that methods leveraging computation will outperform methods using human domain knowledge. In neural networks, human domain knowledge comes in the form of inductive bias, which are design choices that constrain or nudge the network to learn certain solutions. Many have taken the Bitter Lesson to mean that we should strive to eliminate as much inductive bias as possible. But I think that viewing inductive bias as a form of additional data, as Ilya’s quote suggests, reveals a more nuanced lesson. Let us first recount the tale of the Bitter Lesson for (deep) computer vision:

Convolutional neural nets (CNNs) were designed with translation invariance and a bias for spatial locality, as researchers knew these were important properties for understanding images. Meanwhile, vision transformers (ViTs) leveraged a more general self-attention mechanism that can learn global relations between image patches. Although CNNs were more effective on limited data, ViTs ultimately won out when scaled on much more data. And thus came the grand victory of the transformer and the death of the task-specific inductive bias in architecture design, for attention, it seemed, was all we really needed.

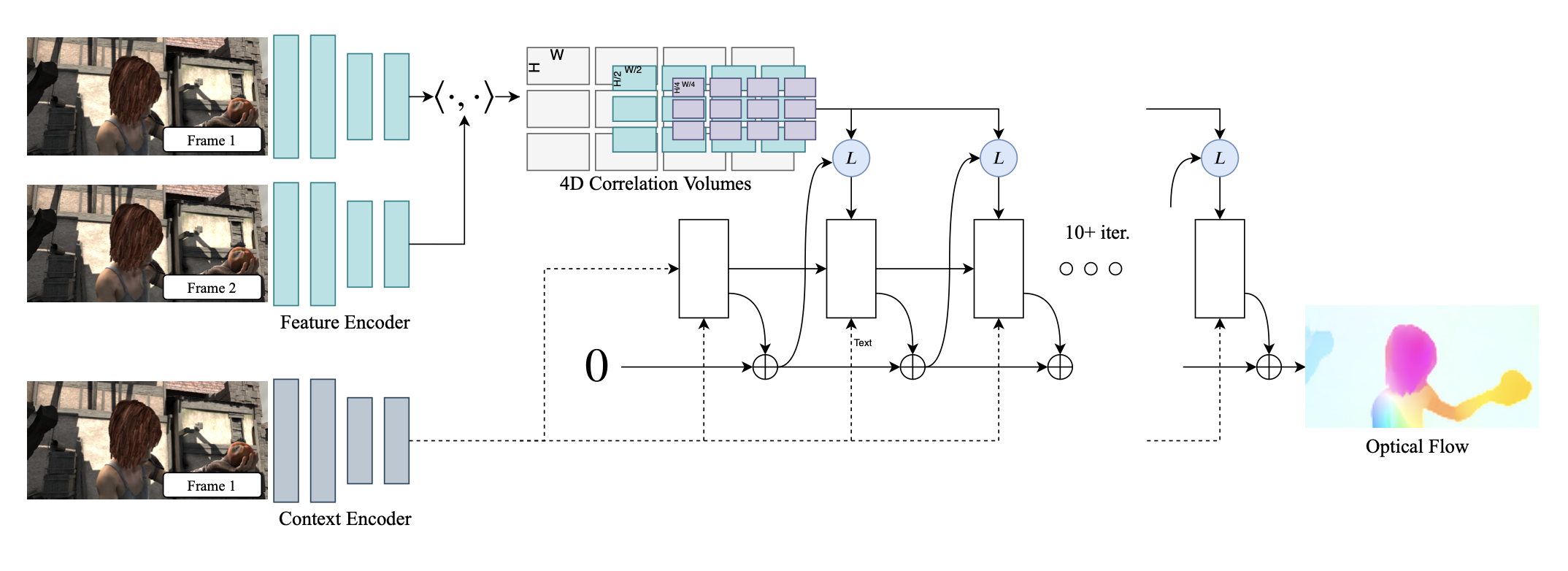

Of course, this is an epic told by the data-rich. In tasks where good training data isn’t plentiful, the evolutionary pressure of data scarcity on model design is evident. Take deep optical flow methods, which have “some of the most involved architectures in the computer vision literature” (Jaegle et al. 2021). In optical flow, we start with two consecutive video frames and want to estimate the $(x,y)$ movement of every pixel between frames. There are two mainstays in optical flow architecture design.

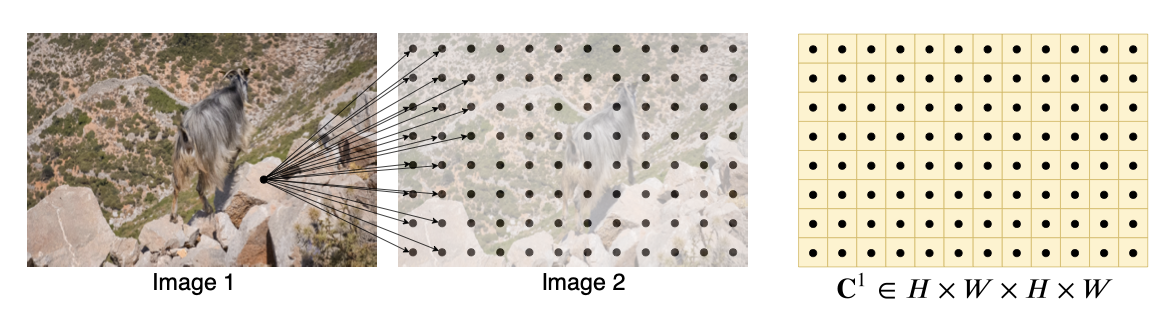

The first is the correlation volume. We know that optical flow involves matching pixels in one image to similar looking pixels in the second image. Therefore, a powerful inductive bias is to bake a matching mechanism into the neural network. Typically, we extract a grid of features from each image and compute the dot product between all cross-image pairs. This process creates a 4-dimensional correlation volume that provides a similarity score for any index $(x_1,y_1,x_2,y_2)$, where $(x_1,y_1)$ is an image patch in the first image, and $(x_2,y_2)$ is an image patch in the second image. This correlation volume can then be further processed or indexed into with a neural network.

The second is iterative refinement. The key idea of iterative refinement is to take a previous estimate of the optical flow and use it to initialize an update toward a better one. This design has its origins in pre-DL flow methods, which formulated flow estimation as an energy-minimization problem computed at multiple image resolutions. The RAFT architecture, shown below, uses both correlation volumes and iterative optimization.

One might wonder why we haven’t converged on the same formula found in many other tasks: encode both images, combine the features, and decode into a dense flow prediction. But it’s not for lack of trying. There have been many great attempts to scale up simpler transformer-based architectures that directly regress flow (see PerceiverIO, CrocoFlow). Despite these efforts, current state-of-the-art performance remains dominated by architectures leveraging task-specific biases. Why is this the case?

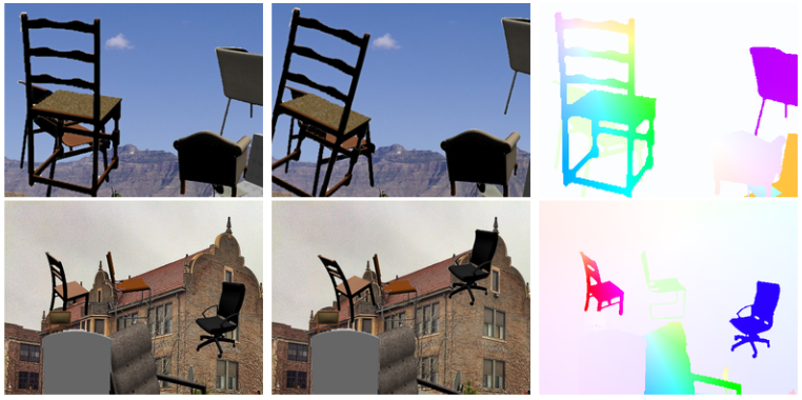

One plausible answer lies, unsurprisingly, within the data. Dense optical flow annotations are extremely difficult to acquire in the real world. As such, it is standard to train on synthetic datasets, which are often highly unrealistic. For instance, FlyingChairs, shown below, is literally just warped images of chairs! Because explicit correlation volumes and iterative refinement provide “extra training data” to aid generalization, methods that leverage these biases beat out the more general designs in this low-data regime.

However, the story doesn’t end there! WAFT is a new work on optical flow from my colleague Yihan Wang. It achieves excellent performance by only using iterative warping, with no correlation volume at all. What does it do differently? It leverages several large pre-trained modules such as DepthAnythingV2 (which itself is based on DINOv2). We can think of transfer learning as another way of acquiring lots of “training data,” this time by leveraging large pre-trained models.

One of the most interesting lessons from WAFT is which inductive bias we lose when we enter this “high-data regime.” It was not iterative refinement, but the correlation volume! This may seem surprising, since the correlation volume seems like the more obvious and useful inductive bias for matching. Meanwhile, the ablation study shows that iterative refinement remains critical for performance. When reallocating the same amount of inference compute to a direct prediction with no updates, the error rate nearly doubles.

This result echoes insights from the late Felix Hill in his blog post The Bittersweet Lesson. He notes that the modal phenomenon of a task is not the one you want to encode as a bias, because an unbiased model will learn it relatively easily. Instead, biases that promote learning and search are more likely to succeed. In the case of optical flow, correlation volumes which model the modal phenomenon of visual similarity become unnecessary, while iterative refinement promotes “search” and stands the test of scale.

If there is one lesson to take away, it is that inductive bias is not anathema. Rather, inductive bias is a parameter we should tune depending on the data constraints of our task. The more data we have, the simpler our biases can be. When we have less data, we can either leverage even stronger biases or acquire surrogate data through a large pre-trained prior. But even in the latter case, there is still value in finding the right biases to adapt the foundation model. The right one might not be the modal phenomenon (e.g. correlation volumes), but it could be a moderate, more scalable bias (e.g. iterative updates).

Of course, it is easier said than done. Finding good biases is hard — the resilience of attention is a testament to that fact. But if we think of data and bias as interchangeable ways to constrain your solution space, it means that a good alternative to working on better biases is working on better data (interpreted broadly). I think this is a particularly exciting research direction. But more on that in a future post!

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Yihan Wang for feedback. Thank you to Felix Hill and the authors of the MIT Vision Book for general inspiration. And of course, thank you to Ted Chiang for writing Hell is the Absence of God, which inspired the title.